Pagoda Blog

The Enigma Machine: A Window Into The History of Encryption

September 7, 2017

|

|

Today, our online banking, text messages, and ecommerce sites all use encryption to ensure our personal information is secure and stays out of the hands of those with malicious intent. Computers power this encryption, scrambling data using complex mathematical formulas in a matter of minutes, but that wasn’t always the case.

In World War II German armed forces had a different method of encryption. They used a device called the Enigma machine to send encrypted messages between Berlin and army commanders in the field. The machine resembled a typewriter and weighed about 26 pounds. It was able to create a staggering 158,962,555,217,826,360,000 (nearly 159 quintillion) and was thought, at first, to be an infallible way to keep classified information from the enemy. A team of 10,000 codebreakers, mostly women, proved the Germans wrong, however, and successfully cracked the Nazi Enigma code.

Before we dive into how the code was cracked, let’s take a look at how the Enigma machine created the code in the first place.

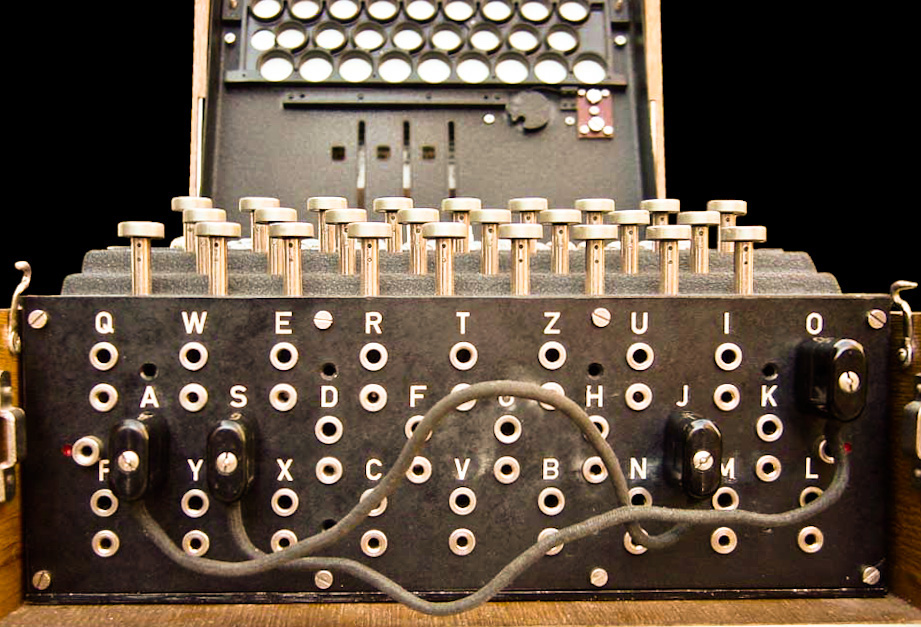

How the Enigma Machine WorksJust like a typewriter, the Enigma machine has a keyboard so that you can easily type out your message. The keyboard is linked to three rotors using an electric current that can transpose each keystroke, effectively working as a random letter generator. This means that the letter ‘A’ for instance, is transposed to a different letter each time. With each keystroke, the transposed letter lights up on a second keyboard called a lampboard. This transposed letter is determined by the starting position of each rotor. Each time you press a key, the rotors move a notch, like the hands of a clock.

The Enigma machine rotors. Photo credit: TedColes [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Each letter on the keyboard is also connected to a plugboard with another series of letters. By moving the wires on the plugboard, you can direct the keyboard to transpose an ‘A’, for example, using the code for the letter ‘Q’ and vice versa, further scrambling the message and making the encryption significantly harder to decrypt. Once the message is typed out and encrypted it’s sent to another Enigma machine via Morse code.

The level of encryption goes even further. Everyday, the creator of the message resets the order of the rotors, their starting positions, and the plugboard connections. This meant that whoever is meant to read the encrypted message has to know the Enigma’s daily settings. In Word War II, the calendar of settings for each month was noted on a piece of paper and hand-delivered by a trusted messenger--a time consuming and highly risky mode of distribution yet it was the securest option available at the time.

Who and What Cracked the Enigma CodeWith trillions of combinations, the Enigma machine was too time consuming to crack using only manpower (or in this case, womanpower). What finally cracked the code, was the effort of thousands of British codebreakers stationed in Bletchley Park with the assistance of a high-speed electro-mechanical device built by mathematician Alan Turing. (The recent film The Imitation Game profiles Alan Turing and his quest to decrypt the Enigma code.)

A codebreaker working the Bombe. Photo credit: National Security Agency [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Inspiration for Turing’s device came from a Polish machine called the bombe. The bombe had 500 electrical relays, 11 miles of wiring, and a million soldered joints to complete the gargantuan task of testing countless hypotheses, or ‘cribs’ against intercepted cryptograms. Cribs were essentially words that were likely to occur in the message and could be determined by the consistent language used in Nazi propaganda. When a crib was guessed correctly, the codebreakers knew they had the key for every encrypted message sent on that day.

This was a long and tedious process but the codebreakers prevailed and historians say their efforts shortened the war by as much as two years. Encryption has come a long way since the Enigma machine and the bombe but these historic devices were still incredibly sophisticated for their time. Remember, the Enigma was capable of creating over a quintillion combinations using rotors and cables. No fancy software required.

To learn more about the Enigma machine check out these articles:

Alan Turing: Codebreaker and Computer Pioneer via History Today Tech Time Warp: Enigma encodes its first message via Intronis Industry and Tech Blog How the Enigma Works via PBS The Enigma Machine Explained [VIDEO] Related Pagoda Posts:

7 Cyber Security Myths Debunked The Basics of Bitcoin and What It Means for Cybersecurity

Featured image by Bob Lord. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

------------------------------

Want to get more posts like these once a month in your inbox? Sign up for the Pagoda newsletter and learn how to protect and grow your business with monthly IT tips from our experts. Subscribe today.

Need ongoing IT support for your business? Contact us for a free consultation. We’d love to work with you!

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– About Pagoda Technologies IT services Based in Santa Cruz, California, Pagoda Technologies provides trusted IT support to businesses and IT departments throughout Silicon Valley, the San Francisco Bay Area and across the globe. To learn how Pagoda Technologies can help your business, email us at support@pagoda-tech.com to schedule a complimentary IT consultation.

|

Return to Pagoda Blog Main Page |